|

The Famished Road Bks 4-8:

Themes, Dreaming, & the African Hermeneutic |

"He who eats well speaks

well, or it is a question of insanity."

"No one knows the mysteries which lie at the bottom of the ocean."

--Yoruba proverbs

I want us to discuss a number of different themes and issues in the

novel, then focus in on a few areas of specific interest. Let us begin, however,

with this excerpt from a recent speech by Okri at the opening of a British Museum show:

We ask why have they [the Iraqi people] turned on themselves,

looted their own museums, and burnt their priceless National Library. The answer is

simple. Some have been dehumanised. They have been broken by sanctions, crushed by tyranny

and annihilated by the doctrine of overwhelming force.

The Aztecs never recovered when Hernan Cortez and the

conquistadores broke the faith of that ancient civilisation. Persia never recovered after

its destruction by Alexander the Great.

The war against Iraq was won in the wrong way. There is a way

to win that does not destroy the ancient mythic pathways of a people. And there is a way

to win that destroys the meaning and value of their past. The worst way to win is when a

defeated people turn on their ancient gods, and tear them down, when a people turn on

their past and burn it. And they don't know why and yet they do. If the past had power and

value why has it brought us to this, is what their actions say. The past has made us

powerless. We need a new kind of power, so that we too can stand proud and with dignity

under the sun.

What does the above suggest about Okri's view of warfare, of

politics, of religion? Is there any evidence of a similar view in The Famished Road?

|

General Discussion Questions

- How does the theme of the road develop in the later half of the

novel? (326-332, 335, 382, 384, 424, 451, 491, 497)

- What role does the land in general and flooding in particular, play

in the work? (cf. 285ff.)

- Equally, how do chaotic events shape Azaro's experience? Why do

they occur? (419-424)

- How does sexual excess act as a threatening power in Azaro's

experience? (272-274, 459-460) What other roles does it play in the novel? (cf. 294)

- How does Azaro's Dad begin to change after he takes up boxing again?

(cf. 397ff.) What is the purpose of his visionary "madness"? (364, 388,

407, 436) His political scheming? (408ff. 419-420, 448)

- How does Madame Koto grow and morph as a character in the later half

of the work? (269, 280-281, 293ff., 304, 360ff., 374, 379ff., 464-467)

- What is the book's message about glory, suffering, and human nature?

(336-338, 344-345, 388, 407)

- What purpose do the beggars play in the book? What is their

connection to Azaro's Dad?

- Why is Nigeria an "abiku country"? (478, 487)

- Why does the novel end the way it does? (500)

Dreaming and Stories

Look over the following excerpts from Okri.

What do they suggest about Okri's approach to dreams, stories, and meaning?

Only those who truly love and who

are truly strong can sustain their lives as a dream. You dwell in your own enchantment.

Life throws stones at you, but your love and your dream change those stones into the

flowers of discovery. Even if you lose, or are defeated by things, you triumph will always

be exemplary. And if no one knows it, then there are places that do. People like you

enrich the dreams of the worlds, and it is dreams that create history. People like you are

unknowing transformers of things, protected by your own fairy-tale, by love.

The acknowledged legislators of the world

take the world as given. They dislike mysteries, for mysteries cannot be coded, or

legislated, and wonder cannot be made into law. And so these legislators police the

accepted frontiers of things.

The greatest religions

convert the world through stories.

The greatest stories are

those that resonate our beginnings and intuit our endings, our mysterious origins and our

numinous destinies, and dissolve them both into one.

The magician and the

politician have much in common: they both have to draw our attention away from what they

are really doing.

The most authentic thing

about us is our capacity to create, to overcome, to endure, to transform, to love and to

be greater than our suffering.

The worst realities of our

age are manufactured realities. It is therefore our task, as creative participants in the

universe, to re dream our world. The fact of possessing imagination means that everything

can be re dreamed. Each reality can have its alternative possibilities. Human beings are

blessed with the necessity of transformation.

To poison a nation, poison

its stories. A demoralised nation tells demoralised stories to itself. Beware of the

storytellers who are not fully conscious of the importance of their gifts, and who are

irresponsible in the application of their art: they could unwittingly help along the

psychic destruction of their people.

We plan our lives

according to a dream that came to us in our childhood, and we find that life alters our

plans. And yet, at the end, from a rare height, we also see that our dream was our fate.

It's just that providence had other ideas as to how we would get there. Destiny plans a

different route, or turns the dream around, as if it were a riddle, and fulfils the dream

in ways we couldn't have expected.

Stories can conquer fear,

you know. They can make the heart bigger.

|

Colonialism

Because we experience the world through the eyes of Azaro, most of

the novel is focused on the limited world of the ghetto, along with Azaro's trips into the

spirit world. Only on occasion does the larger colonial experience of

pre-Independence Nigeria enter into the work. However, it seems to take on a real

significance in one of Azaro's visions , as well as the reflections of Azaro's Dad near

the end of the work. Look closely at pages 455-457 and pages 492-494.

Summarize the substance of these pages. What do they reveal about the forces

and impact of colonialism? |

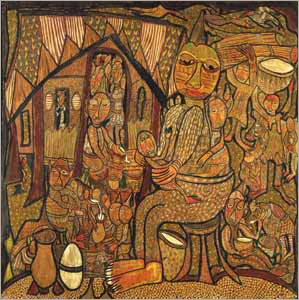

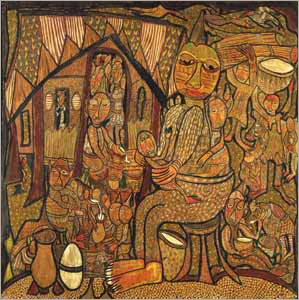

Healing of

the Abiku Children, 1973 |

|

Magical Beings & Other Religious Themes What is the significance or importance of the following magical (or at least

marvelous) persons in the book?

- The three-headed spirit (297, 302, 326)

- The blind old man (313, 319-322, 465)

- The beggar girl (453-453, 466-467)

- Ade (368-370, 476, 485-486)

- Yellow Jaguar (355ff.)

- The boxer/thug in the white suit (468ff.)

- The white man who turns African

|

- Compare and contrast the portrayal of Christianity in these two

scenes: pages 281-283 & 375-378.

- What does Azaro's vision of a beautiful woman signify? (307-308)

- What is the significance of the spirit's view of God and the gods on

page 332?

- How is time understood in the novel? (281-283, 292, 484)

- What is the substance of Azaro's Dad's final religious views?

(498-499)

|

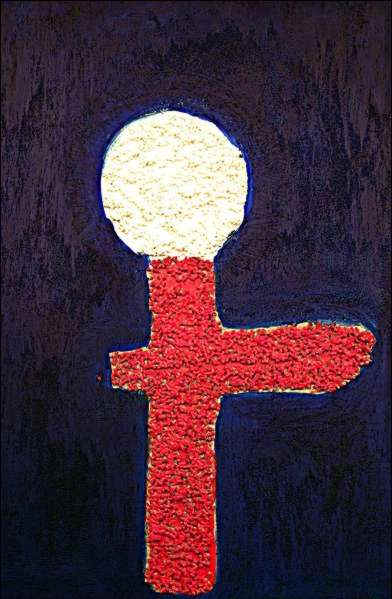

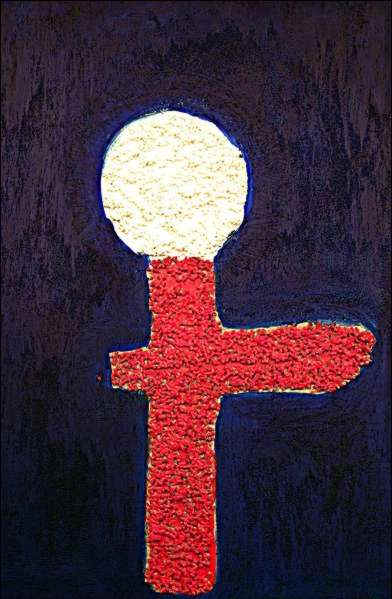

Esu & the African

Hermeneutic

Henry Loius Gates, Jr. in his book The Signifying

Monkey argues that an African hermeneutic or approach to interpretation and discourse

is found in African-American literature and life. His discussion of the African

approach is particularly revealing of certain aspects of Okri's approach in The

Famished Road. |

|

Gates looks to Esu's role in Yoruban

cosmology as a trickster figure and a mediator. He also looks to use of the ifa

divination tray. Sixteen stones are placed in the tray, shaken, and then interpreted

in a fashion not unlike the I Ching. Gates pulls these and other elements

together to posit an African hermeneutic that values "direction through

indirection," figurative play, and a double-voicing, where things always have

multiple meanings. In his understanding, the African hermeneutic never claims direct

access to the truth because Esu (trickery/play) always governs understanding. He

concludes:

- That a tension always exists between oral and written forms of

understanding, the oral being more fluid and more double-voiced.

- That such a hermeneutic privileges the figurative and the principled

over the literal and polemical.

- That indeterminacy is basic to the interpretative process.

[Click here for excerpts from

Gates' book.]

Questions: Is such a hermeneutic at play in Okri's

novel? (cf. 4487-488) What connection does Esu have with the experience of chaos and

the road? Does Okri's notion of dreaming coincide in any way with Gates' discussion? |

|