The Harlem

Renaissance and The Question of Cultural Representation |

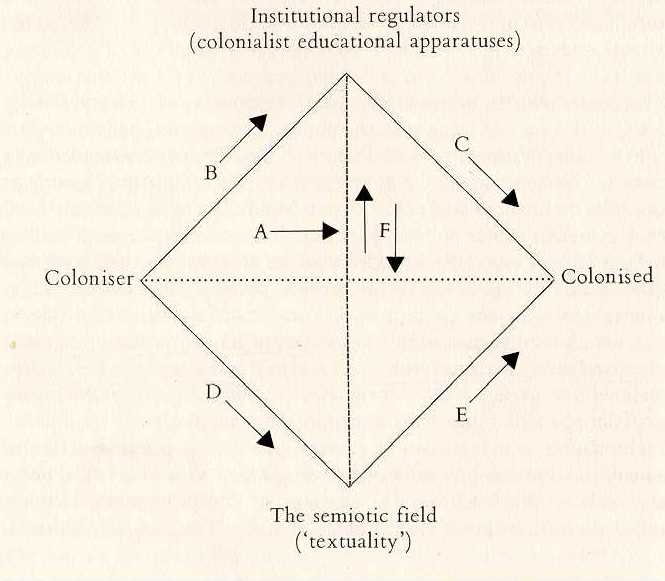

| Authors, artists, musicians, educators, and political activists of the Harlem Renaissance struggled with how to best reflect, embody, and even create an authentic culture for the African-American community. One difficulty they faced was how to go about offering literary portraits of people and their lives without playing into the hands of stereotypical expectations of their often largely white audience. The following diagram, while deriving from postcolonial studies, represents some of the factors they faced: |

|

| "Institutional regulators" signifies the

means of cultural education that the dominant oppressor culture has instituted. This

includes schools, churches, clubs and organizations, businesses -- any organization that

teaches what is and is not known, accepted, and understood as cultural givens. "The semiotic field" signifies methods of cultural representation -- books, music, portraits, popular images and icons, theatre, etc. A represents the direct political power and control a dominant group has over an oppressed group. B and C represents the way a dominant group shapes an oppressed group's social standing, intellectual advancement, even self-perception through a control of what is acceptable knowledge and behavior. D and E represents how cultural representation also does this by perpetuating certain behaviors and images of a people. F represents the reciprocal relationship between those institutions of cultural education and those expressions of cultural representation.

What this diagram doesn't express is the ways in which the colonized, the oppressed, resist this education and representation. These methods tend to take on three different manifestations: 1) subversion of the existing language and images by reappropriating them for new purposes; 2) the valorization and/or creation of alternate indigenous forms intrinsic to that community; and 3) a genuine hybridity of form that takes aspects of the oppressor's institutions, language, and images and marries them in new ways with aspects intrinsic to the oppressed's culture.

Click here to look at the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute site on the Harlem Renaissance. |