Auden's Struggle with Love and Desire

|

|

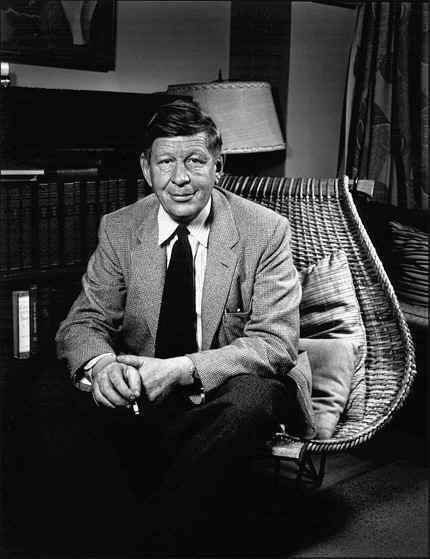

| W. H. Auden from 1940 to 1942, the same years as his

return to the Anglican church, wrote a number of poems that struggle with the conflict

between self-willed love and grace-given love. The former he suggested is really

only a mask for our desires and need to rule ourselves. It inevitably results in

personal, and even political, violence. The later is a gift of grace, involves

forgiveness, a sense of our limitations, and is accompanied by suffering. It is best

expressed by praise, which calls us out from ourselves. Commentary "The Dark Years" Set against the backdrop of WWII, "The Dark Years" looks at the world of violence and death and compares the responses of that of the ego-driven will and that of grace-inspired praise. stanzas 1-8: set the stage for the ego's disappointment at the "world of time" (daily life) in comparison to the timeless world of dreams. Auden speaks in understated ways of war's conditions: "the noise or the people," "shadows with enormous grudges," "whipping websters" (the Fates), "the changing complexion along with the woods," "while blizzards havoc the garden." stanzas 9-11: The ego wishes to return to the world as ideal--"hanging gardens of Eros/ and the moons of a magical summer." But instead, one is in a world as a labyrinth, where "either/ we are found or lose ourselves for ever." stanzas 12-14: What way are we to follow before such bewildering times, times that promise us death? Auden contrasts Jesus with the Judas-like betrayal of the existential abyss. stanzas 15-18: Before such a situation, repentance ("formal contrition") is needed; we need to embrace both the positive and negative ways of knowing God. We need to praise God in his infinite eternity, as well as Christ the Logos' incarnation in human flesh. Auden in particular focuses on John chapter one in the last few lines. "In Sickness and in Health" A meditation on the conditions of love and (via the title) marriage, "In Sickness and in Health" compares the conditions of a destructive, self-serving love with the conditions of a sacrificial, reasonable marriage. stanzas 1-4: Forgiveness is essential; without it, one is making only surface-level claims about love. We especially need to remember this in a time of war when satanic forces ("the Black Dog") are subjecting the world to such famine and destruction. The kingdom of Eros is, likewise, a kingdom of famine and destruction. Its world is that of "warped mirrors" in which the lovers see themselves and of a "will-to-order." One can only love when one truly understands the costs is caring for another life, "a ruining speck, one tiny hair." stanzas 5-6: Auden examines two different myths of sexual illusion and predation. The lovers Tristan and Isolde put off consummation and thereby build up to their final passion, then die rather than let Isolde's maid, Brangaene, call them back to mundane love. Don Juan moves from lover to lover-- like " a helpless, blind/ Unhappy spook, he haunts the urinals." Auden suggests that both of these distortions lead to a political sublimation of desire, where "the disobedient phallus" is substituted "for the sword." stanzas 7-9: True love asks us to approach each other from a position of weakness. Auden quotes Kierkegaard: "Before God, we are always in the wrong." In the face of our petty, selfish loves which are tohu-bohu ("without form and void" Gen 1:2), we are commanded by Christ to rejoice, for it is rejoicing that brings form to our void, that teaches the dance its pattern. Our loves "exist by grace of the Absurd." Only a vow will keep us from trying to be little gods. stanzas 10-12: Self-praise is but a form of sublimated desire. Auden prays that God ("O Essence of creation") might move us to seek him in the physical world. Yet so that we do not make the mistake Paul describes in Romans chapter one of worshipping the creation instead of the Creator, may we be moved with a love of God in our "intellectual motions." [Is there an implicit dualism here?] stanzas 13-14: The "round O of faithfulness" is both spiritual ecstasy and the wedding band. Auden prays that such a commitment never end up an empty form that mocks real virtue and exposes itself to temptation. Over against romance, Auden recommends sober love that is preserved "from presumption and delay." Our future, like the Christian kiss of greeting (felix osculum), should remain mysterious; better to walk in "the ordinary way." "Many Happy Returns" A birthday celebration for John Rettger, age seven, son of James Rettger (a professor of English at University of Michigan, Ann Arbor the same time as Auden). "Many Happy Returns" is a study in our playacting in the world, one that can be given over to pride or a sense of our limitations. stanzas 1-7: After toying with the astrological signs of their birthdays, Auden playfully suggests to John that he learn how to see life as a kind of stage where everyone is acting to some extent. However, beware because such knowledge can lead to "Man's unique temptation," which is pride. Only God can give someone a new or different role in the play of life. stanzas 8-10: Birthdays, then, are a kind of allowable playing at pride because they also remind us of our limitations as human beings. stanzas 11-18: It would be a mistake to wish him success; he should be aware of his own troubles and not be ashamed of suffering. Wit needs sorrow. Self-knowledge is a kind of temptation, which Auden sets over against Whitehead's notion of "negative prehension," a kind of tacit way that cultures go about important things without being self-aware of them. Instead Auden wishes for John a balanced life (Tao)--intellect with the senses ; Socratic questions with the Socratic assurance of the daimon. "Mundus et Infans" This poem explores the delights and natural selfishness of infancy, as well as the differences between such a hunger and true love. stanzas 1-3: Auden touches on the child who kicks the mother in the womb, demands his milk for free, sleeps, and operates in a world where no distinctions are yet made between oneself and others. stanzas 4-5: The advantage of this state is that an infant is completely honest (like the saints) and exists without shame. stanzas 6-7: The infant's very being (cries and bowel movements) praises God the Creator. His demands remind us again and again that love is self-sacrificial, unlike infant hunger. "Canzone" A sadder, more melancholy poem, "Canzone" explores the rage and anger of eros, its self-will and hidden needs. The poem ends looking to praise and God as a way to establish true love. stanzas 1-3: Love is not freely chosen, and we were created "from and with the world." Even our bodies are not really our own. Our erotic appetites express themselves in all kinds of rage, regret, fury, and political catastrophe, and what we think is love is really the desire to choose or not choose to love. stanzas 4-7: Our self-will is haunted and deceptive, and the mirror of love is really a revelation of our chaotic selves, our "blind monsters." True love doesn't excuse misdeeds done in love's name. We are to praise God that our trails not be wasted, and we are to set aside our self-will that true love may grow by its sorrow. Questions

|

|