|

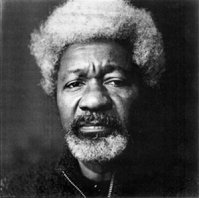

Soyinka, Ogun, and Christ |

Death and the King's Horseman

can be read without

any detailed knowledge of Soyinka's own religious positions, yet the following may be helpful

in understanding Soyinka's judgments concerning certain aspects of religion

in the play:

From William McPherson's Introduction to Soyinka "At its center and guiding its artistic mission lies the idea of "organic revolution," which Soyinka contrasts with the neocolonial practices that black Africa absorbed from European imperialism. As he defines the concept, organic revolution is a process of communal renewal reached in moments of shared cultural self-apprehension -- moments whose manner and content are particular to each society. Such revolution is inherently local and cyclical, qualities more appropriate to African culture, Soyinka argues, than the global teleologies of either Marxist communism or capitalist nationalism. Indeed, Soyinka's mode of liberation ultimately displaces the logic of Western politics with the rhythms of native ritual. For the revolution he advocates rejects the abstractions of both dialectical materialism and market economics for the particularity of ceremonial healing -- of the divisions that isolate individuals from society and sever both from their sustaining integration with nature. The god whose ritual Soyinka offers as the model for this organic restoration is Ogun , who risks his own life to bridge the abysses that separate the three stages of Yoruba existence -- the world of the ancestors, the world of the living, and the world of the unborn. Ogun, as Soyinka reads the myth, is unique among tribal deities because he is at home in none of these three structured states of experience. Rather, his realm is the chaotic region of transition between them, what Soyinka calls the "fourth stage" of the Yoruba universe, a condition where opposites collide without resolution in "a menacing maul of chthonic strength that yawns ever wider to annihilate" all social and natural order. Ogun's heroic passage through this realm not only preserves the connections between the ancestors, the living, and the unborn. It also revitalizes the Yoruba cosmos by benignly channeling into it fresh energies from the fourth stage. This model of social revolution is essentially one of recurring crisis, where novel and alien forces are regularly mastered and integrated into the matrix of tradition and custom. It is to the challenge of this crisis that Soyinka commits his art, and only within its context can the signature gestures of his style achieve their full meaning. But once seen in the framework of Ogun's encounter with the fourth stage, Soyinka's discordant mixing of genres, his willful ambiguities of meaning, his unresolved clashes of contradictions cease to be the aesthetic flaws Western critics often label them and become instead our path into an African reality fiercely itself and utterly other. " Soyinka on Christ as a Symbol "This, again, I believe is part of the pattern of acceptance of European thought and ideas -- this idea of attributing the concept of self-sacrifice to the Christian, to the Euro-Christian or Judeo-Christian world, simply because a single figure emerged from that particular culture to espouse, in very beautiful mythological terms, the cause of the self-sacrificing individual as a kind of, as the surrogate for world suffering, social unhappiness, and general human unhappiness. It is often forgotten that the idea of individual sacrifice-the principle of the surrogate individual-is, in fact, a "pagan" one. Those who attribute this concept to Europe forget that Christianity itself is not a European religion. And that Christ, the central figure of Christianity, is really a glamorization of very "paganistic" ideas: the idea of personalizing the dying old year, the dying season; to insure the sprouting, the fertility, the idea of the emergence, in fact the very resurrection, of Nature. All this is "pagan" -- "pagan" as an expression used by the Christian world to describe the fundamentally natural, Nature religions. I see Christianity merely as another expression of nature religion. I cannot accept, I do not regard the principle of sacrifice as belonging to the European world. I completely reject the idea that the notion of the scapegoat is a Christian idea. This scapegoat idea is very much rooted in African religion...I think the obsession with individual salvation -- which, if you like, is on the opposite end of the axis to self-sacrifice -- is a very European thing. I am not aware that it occupied the minds of our people. I think it is a very European literary idea; in fact, the obsession itself is a very Christian principle. In our society, this kind of event, this process, is inbuilt into the very mechanism which operates the entire totality of society. The individual acts as a carrier and who knows very well what is going to become of him is really no different, is doing nothing special, from the other members of society who build society and who guarantee survival of society in their own way. I think there is one principle, one essential morality of African society which we must always bear in mind, and that is the greatest morality is what makes the entire society survive. The actual detailed mechanism of this process merely differs from group to group and from section to section, but it is the totality that is important. I think there is far too much concern about this business of the Christian ethic of individual self-sacrifice. " Interview by Louis S. Gates. Black World, v 24, #10 (August, 1975 ) Soyinka insists that the principle of sacrifice and the scapegoat

are not European things nor endemic to Christianity alone. For him, Christ is but a

symbol of these things. He also argues that African religion is more concerned with

communal salvation and not individual sacrifice. The Ethics of the Theatre "First of all I believe implicitly that any work of art which opens out the horizons of the human mind, the human intellect is by its very nature a force for change, a medium for change. In the black community here, theater can be used and has been used as a form of purgation, it has been used cathartically; it has been used to make the black man in this society work out his historical experience and literally purge himself at the altar of self-realization. This is one use to which it can be put. The other use, the other revolutionary use, may be far less overt, far less didactic, and less self-conscious. It has to do very simply with opening up the sensibilities of the black man not merely towards very profound and fundamental truths of his origin that are in Africa in suddenly opening him...to new experiences...as a means of making the audience question an identity which was taken for so long for granted, suddenly opening the audience up to a new existence, a new scale of values, a new self-submission, a communal rapport. By making the audience or a member of the audience go through this process, a reawakening has begun in the individual which in turn affects his attitude to the external social realities. This for me is a revolutionary purpose...Finally and most importantly, theater is revolutionary when it awakens the individual in the audience, in the black community in this case, who for so long has tended to express his frustrated creativity in certain self-destructive ways, when it opens up to him the very possibility of participating creatively himself in this larger communal process. In other words, and this has been proven time and time again, new people who never believed that they even possessed the gift of self expression become creative and this in turn activates other energies within the individual. I believe the creative process is the most energizing. And that is why it is so intimately related to the process of revolution within society." Interview edited by Karen L. Morell, April, 1974 Soyinka argues that theatre has for the African three important ethical values:

Exploratory Questions

Overview Questions

|

|