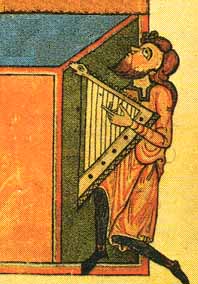

| ORPHEUS was the son of Apollo and the

Muse Calliope. He was presented by his father with a Lyre and taught

to play upon it, which he did to such perfection that nothing could

withstand the charm of his music. Not only his fellow-mortals but

wild beasts were softened by his strains, and gathering round him

laid by their fierceness, and stood entranced with his lay. Nay, the

very trees and rocks were sensible to the charm. The former crowded

round him and the latter relaxed somewhat of their hardness,

softened by his notes.

Hymen had been called to

bless with his presence the nuptials of Orpheus with Eurydice; but

though he attended, he brought no happy omens with him. His very

torch smoked and brought tears into their eyes. In coincidence with

such prognostics, Eurydice, shortly after her marriage, while

wandering with the nymphs, her companions, was seen by the shepherd

Aristæus, who was struck with her beauty and made advances to

her. She fled, and in flying trod upon a snake in the grass, was

bitten in the foot, and died. Orpheus sang his grief to all who

breathed the upper air, both gods and men, and finding it all

unavailing resolved to seek his wife in the regions of the dead. He

descended by a cave situated on the side of the promontory of Tænarus

and arrived at the Stygian realm. He passed through crowds of ghosts

and presented himself before the throne of Pluto and Proserpine.

Accompanying the words with the lyre, he sung, “O deities of the

underworld, to whom all we who live must come, hear my words, for

they are true. I come not to spy out the secrets of Tartarus, nor to

try my strength against the three-headed dog with snaky hair who

guards the entrance. I come to seek my wife, whose opening years the

poisonous viper’s fang has brought to an untimely end. Love has

led me here, Love, a god all powerful with us who dwell on the

earth, and, if old traditions say true, not less so here. I implore

you by these abodes full of terror, these realms of silence and

uncreated things, unite again the thread of Eurydice’s life. We

all are destined to you, and sooner or later must pass to your

domain. She too, when she shall have filled her term of life, will

rightly be yours. But till then grant her to me, I beseech you. If

you deny me I cannot return alone; you shall triumph in the death of

us both.”

As he sang these tender

strains, the very ghosts shed tears. Tantalus, in spite of his

thirst, stopped for a moment his efforts for water, Ixion’s wheel

stood still, the vulture ceased to tear the giant’s liver, the

daughters of Danaüs rested from their task of drawing water in a

sieve, and Sisyphus sat on his rock to listen. Then for the first

time, it is said, the cheeks of the Furies were wet with tears.

Proserpine could not resist, and Pluto himself gave way. Eurydice

was called. She came from among the new-arrived ghosts, limping with

her wounded foot. Orpheus was permitted to take her away with him on

one condition, that he should not turn around to look at her till

they should have reached the upper air. Under this condition they

proceeded on

their way, he leading, she following, through passages dark and

steep, in total silence, till they had nearly reached the outlet

into the cheerful upper world, when Orpheus, in a moment of

forgetfulness, to assure himself that she was still following, cast

a glance behind him, when instantly she was borne away. Stretching

out their arms to embrace each other, they grasped only the air!

Dying now a second time, she yet cannot reproach her husband, for

how can she blame his impatience to behold her? “Farewell,” she

said, “a last farewell,”—and was hurried away, so fast that

the sound hardly reached his ears.

Orpheus endeavored to

follow her, and besought permission to return and try once more for

her release; but the stern ferryman repulsed him and refused

passage. Seven days he lingered about the brink, without food or

sleep; then bitterly accusing of cruelty the powers of Erebus, he

sang his complaints to the rocks and mountains, melting the hearts

of tigers and moving the oaks from their stations. He held himself

aloof from womankind, dwelling constantly on the recollection of his

sad mischance. The Thracian maidens tried their best to captivate

him, but he repulsed their advances. They bore with him as long as

they could; but finding him insensible one day, excited by the rites

of Bacchus, one of them exclaimed, “See yonder our despiser!”

and threw at him her javelin. The weapon, as soon as it came within

the sound of his lyre, fell harmless at his feet. So did also the

stones that they threw at him. But the women raised a scream and

drowned the voice of the music, and then the missiles reached him

and soon were stained with his blood. The maniacs tore him limb from

limb, and threw his head and his lyre into the river Hebrus, down

which they floated, murmuring sad music, to which the shores

responded a plaintive symphony. The Muses gathered up the fragments

of his body and buried them at Libethra, where the nightingale is

said to sing over his grave more sweetly than in any other part of

Greece. His lyre was placed by Jupiter among the stars. His shade

passed a second time to Tartarus, where he sought out his Eurydice

and embraced her

with eager arms. They roam the happy fields together now, sometimes

he leading, sometimes she; and Orpheus gazes as much as he will upon

her, no longer incurring a penalty for a thoughtless glance.

|