The Bible, the Land, and Postcolonial Mapping |

The mapping of global space in the context of colonialism was as much prescriptive as it was descriptive. Maps were used to assist in the process of aggression, and they were also used to establish claims, such as the boundaries of modern nation-states. Mapping serves any number of purposes, but what postcolonial theory reminds us is that it is not an "objective" source of information; maps are created with specific goals and beliefs in mind. Consider the following three maps of the Great Sandy Desert of Northwestern Australia, an area which the Aboriginal inhabitants describe as jila (springs) and jilji (sand dunes), and which they divide into various regions, such as Japingka. |

|

|

|

|

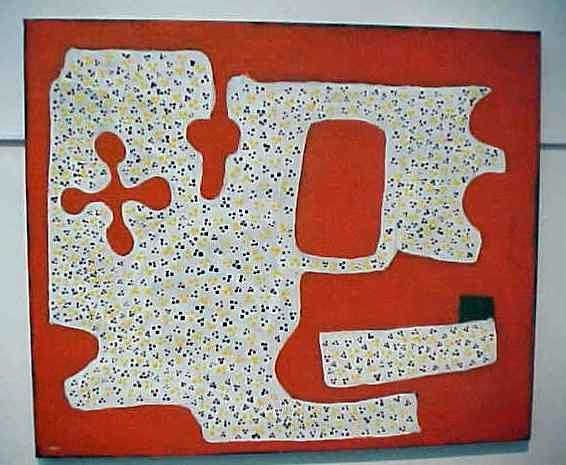

| The first map on the upper left is a topographic map used by national park services and scientists to establish general ecosystems. The second on the right is a tourist map that shows sights of interest for outbackers. The third on the lower left is a painting by Peter Skipper, a Juwaliny / Walmajarri man who was born in the region. The work is called Japingka Area. [Visit Peter Skipper's art project site.] Each map has a different purpose and even suggests a different worldview. The first classifies the area according to "semifixed linear dunes" and "dune free" areas. The second map stresses the place names that modern Australians have given the region, while the third by Skipper is more concerned with reflecting on the emotional impact of the land. The cross-shape represents the four directions, west being on top; the other shapes represent jilaI, living waters, jilia, sand dunes, and a large warla, or claypan salt lake. These represent sources of life and death, as well as movement and exile, for the people of the Japingka. The three maps are thus motivated by a scientific understanding, a commercial understanding, and a regional/native understanding. | |

At the center of such issues as mapping are specific beliefs about how one defines the land and what relationship human beings have with it. Space represents a geographic locale, one empty in not being designated. Place, on the other hand, is what happens when a space is made or owned and, thus, involves landscape, language, environment, and culture.. When we map something we are designating what a certain space is, and designating what a space is also tells us what we perceive our relationship to that space to be. A place is for something. In the cases above, the first map tells us the space in question is an object of study; the second sees it as a destination for curiosity and tourism; the third believes it to be a place of survival and homeland. Old colonial maps often reveal elements of early European attitudes towards Africa, the Caribbean, etc. For example, early mapmakers would locate monsters and cannibals in such regions. But even when a map was limited to (and fairly true to) topography, the very act of naming a space declared it to be something other than what the original inhabitants deemed it to be, and such maps served European interests. Not only did they serve political, military, and cultural conquest, they also functioned as tools of hegemony because they dictated to subjugated peoples the names and woldviews through which they should view their region and even themselves. |

|

|

All this is not to say that maps are inherently destructive or malevolent. But it is to suggest that maps are more than just neutral tools; they carry worldviews attached to them, and as such, they have import as to how we view and treat spaces. What, then, might a biblical understanding of the land have to say, even by analogy, to the practice of mapping postcolonial spaces and places? Walter Brueggemann in his important 1977 socio-critical study, The Land, looked at how place is central to the biblical faith of Israel, and by extension, to the Christian Church. Brueggemann uses the terms "space" and "place" in a similar but not entirely synonymous way to how I have used them above. Space, for Brueggemann is not only an undesignated geographical locale, it is also "an arena of freedom, without coercion or accountability, free of pressures and void of authority, " while place "has historical meanings [. . .] which provide continuity and identity across generations." In the Jewish experience, the promised land is always the receptacle of shalom:

The land becomes the physical, social, and symbolic conduit for identity, responsibility, and blessing. The Old Testament, in one sense, may be understood as Israel's memory of both her states of landlessness and landedness. Israel's experience of landlessness includes:

Likewise, Israel's landedness may be seen in three periods:

The New Testament Christian church has a kind of continuity with Israel's memory, for in one sense, the church is an entity engrafted into Israel (Rom 11:11-24, Eph 2:11-13), while in another sense the church is Israel, the people of God (Gal 6:14-16, Eph 2:14-22). The church, like Israel, experiences both sojourn (Heb 13:11-13) and the hope of a land (Heb 12:14-24, Rev 21), and the larger New Testament vision is one that expands the landedness of Israel to the whole creation (Rom 8:18-25, Eph 1:18-23). Of course, this is not to say that the Old Testament ignores God's rule of all creation (Gen 1-2, Ps 96, Is 40:21-32). Nonetheless, there is a renewed sense with Jesus that the expectation of shalom is now a global one (Col 1:15-20, II Pet 3, Rev 21). God will judge, then condemn or restore all things. As we can see, the experience of Israel was both a land-bound and a land-free one, always embodied and local, yet also faith enacting and God-dependent. Israel's memory "maps," if you will, the geographic space they reside in or wish to come/return to. This experience reminds us that a space becomes a place for good and for evil reasons. As we have been suggesting this semester, the creational principle of interdependence, the diversity and hybridity of church, scripture, and faith, and the biblical models of personhood and shalom all remind us that local embodiments of a people are both changing over time and also very valuable. (Each in a sense always continues to exist before the perception of God.) Mapping may be used for good if its telos is shalom and carries with it the ends of responsible stewardship and respect for human rights as an expression of the imago dei. Yet mapping may also result in violations of shalom, denials of human dignity, and worldviews that offer corrupt notions of personhood. I don't believe we can extend the particular experience of landlessness of Israel to other similar experiences of postcolonial peoples, yet we can offer as Christians to all peoples the resulting hope for a blessed land, faith as dependence upon God's provision, and love of the good gifts of God. In that sense, Israel's struggle with living in the land is the struggle of every ethnoi in learning to practice justice and acknowledge its rightful standing before the Creator. Likewise, to borrow Volf's terminology again, the catholic and evangelical personalities of Christians should call them to hold two maps in their lives--a local map and a universal one. As Christians of every people participate in the life of that people, they are to stand with yet apart, receiving the other, yet calling the locale to repentance. What would, I wonder, a shalom map of a place pay attention to? Brueggemann, Walter. The Land: Place as Gift, Promise, and Challenge in Biblical Faith. Philadelphia: Fortress, 1977. |

|